Frankye Adams-Johnson: Black Panther From Mississippi

Introduction

Many people, when they think of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPP), have images of activists either in the northern part of the United States or in California. In reality, the BPP was active all over the country in the 1960's and 1970's. And, many young activists from the South went north and west in the 1960's to join up with and even start local BPP chapters. One such young activist was Frankye Adams-Johnson. Forged in the flames of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi, as a college student she moved to New York where her activism and community work entered a brand new, yet familiar, phase.

Frankye Adams-Johnson was born in Pocahontas, Mississippi, to a family of sharecroppers. As a teenager in Jackson, Mississippi, she participated in the NAACP, COFO, and SNCC as a youth organizer and was heavily involved in the Jackson civil rights movement in 1963. In 1964, she enrolled at Tougaloo College where she continued to be involved in civil rights demonstrations. After moving to New York in 1967, she co-organized the White Plains branch of the Black Panther Party. Adams-Johnson became a college professor in the 1980s, and returned to Jackson from New York in 1999, where she began work as an adjunct professor at Jackson State University in 1999. She became a full-time professor in 2003 until retiring in 2014.

From Mississippi to New York

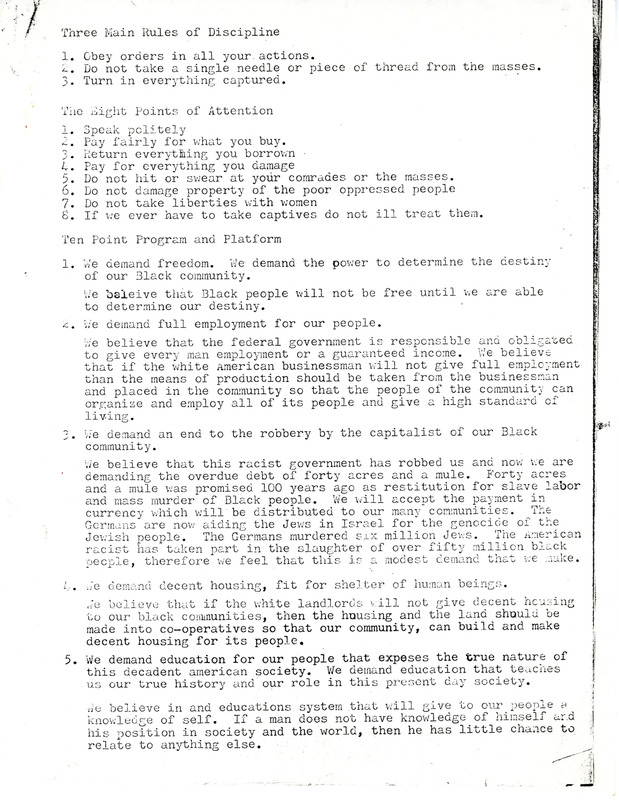

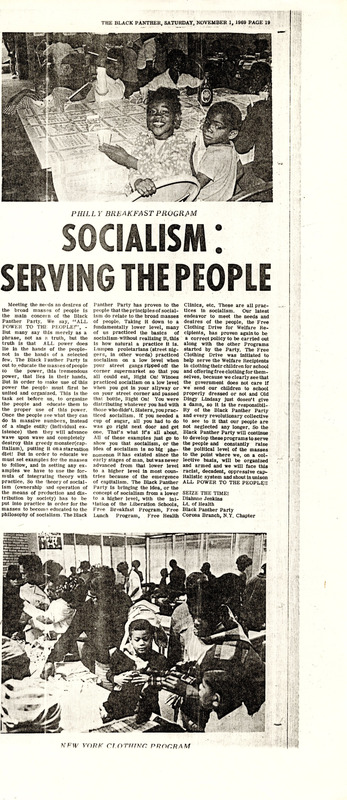

While in high school in Mississippi, she began attending NAACP meetings and soon was organizing a walk-out at her school; she was arrested with a group of students just a quarter mile from their school and held in livestock stalls at the Mississippi State Fairgrounds in Jackson. She was arrested again while marching after the assassination of Medgar Evers in 1963. Later that summer she traveled to Washington, D.C., for Martin Luther King’s March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, an experience that had a profound impact on her. In 1964 she enrolled at Tougaloo College, an HBCU in Jackson, Mississippi, but was kicked out of her music program for being involved in activism. Her mother, worried about her daughter’s safety in Mississippi, sent her to live with family in White Plains, New York, where the Black Panther Party helped her set up a local chapter. She remained active with the Panthers until the Party split in 1971. One of the most important issues to her was breakfast programs for school children and with the Black Panther Party she was able to help provide that service.

Black Panther Party and the Black Liberation Army (BLA)

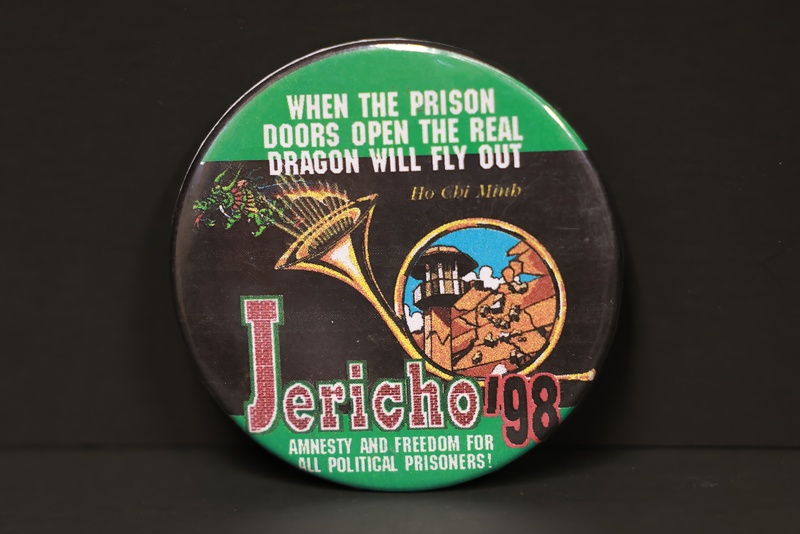

In 1971, the Black Panther party split and one faction took on a more radical, Black Nationalist tone, with many adherents subscribing to the use of the tactic of violence against the government and police and robberies to find activities. As Frankye Adams-Johnson was trying to find her place in the post-Party world, she found herself aligned with the beliefs of underground splinter groups, especially the Black Liberation Army (BLA) which had formed in 1970 as the underground armed wing of the Black Panther Party. Multiple members of the BLA were arrested and convicted for murder, robbery, and a host of other charges. Because of the government’s use of police brutality and illegal surveillance and propaganda tactics such as COINTELPRO, and the BLA’s assertion that they were at war with the United States government, many of the incarcerated BLA members were considered political prisoners and prisoners of war.

Political Prisoners

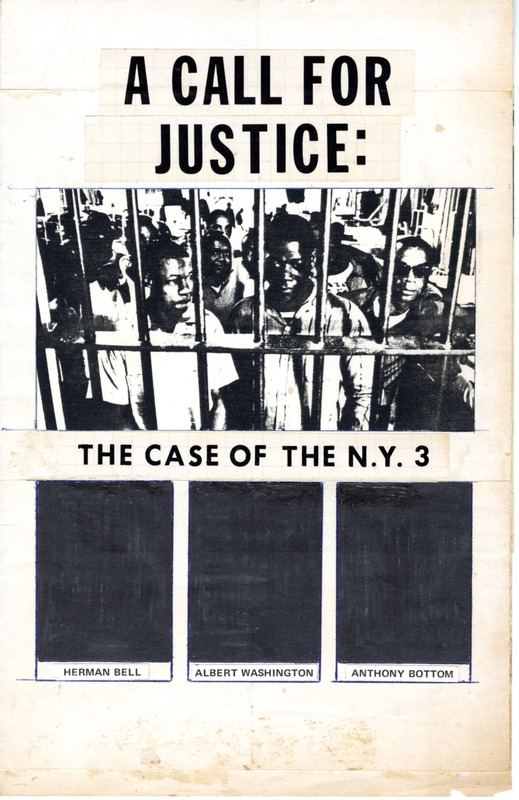

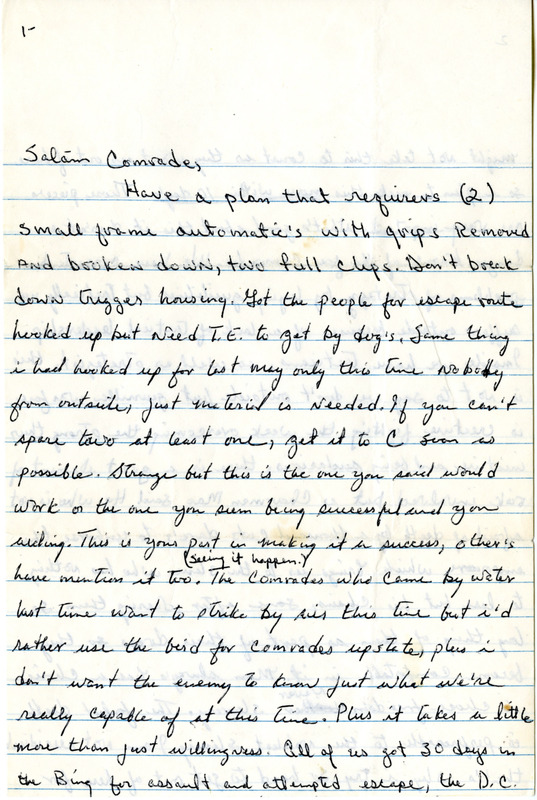

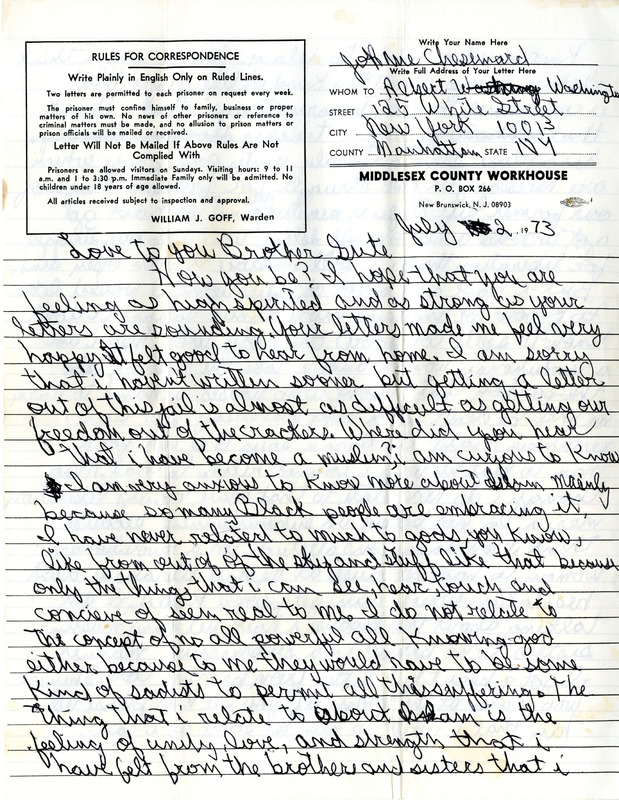

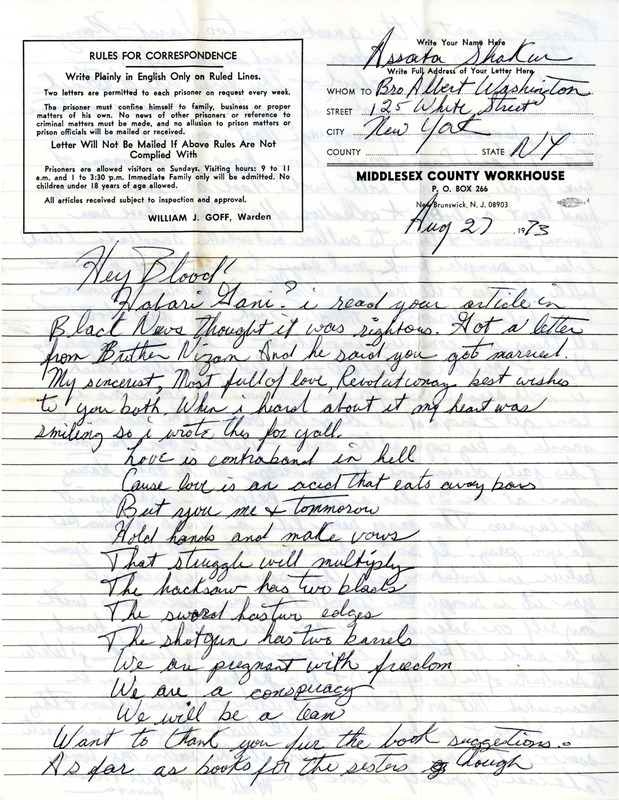

Eventually, Frankye Admas-Johnson began a relationship with BLA member Albert Washington, aka Nuh Abdul Qaiyum (“Nuh” is the Arabic pronunciation of Noah). Qaiyum, along with Herman Bell and Anthony Bottom, were sentenced to 25 years to life in federal prison for the murder of two cops in 1971. Because of the use of COINTELPRO and some shady evidence, the three were considered political prisoners and became known as The New York 3. While imprisoned, Qaiyum exchanged letters with several other political prisoners including Sundiata Acoli, Gunnie Haskins, Assata Shakur (Joanne Chesimard), and others. He also maintained correspondence with Frankye Adams-Johnson until their relationship fell apart due to his imprisonment. At one point, he wrote her a letter with a list of materials he needed for an attempted escape from prison.

Going Underground and the Years That Followed

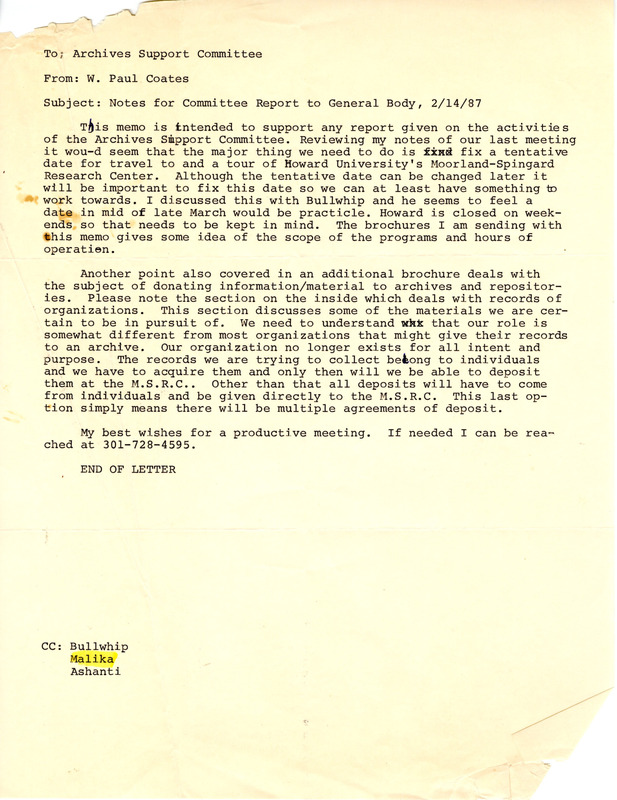

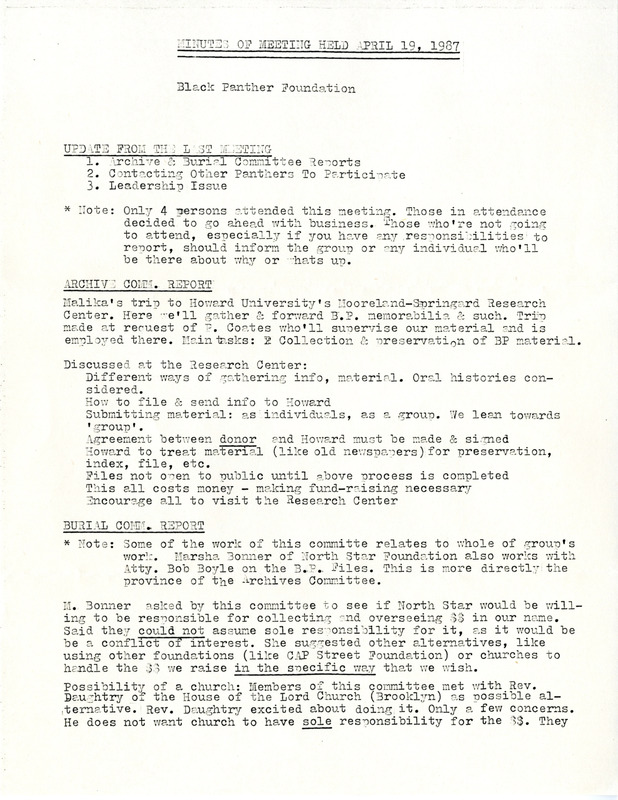

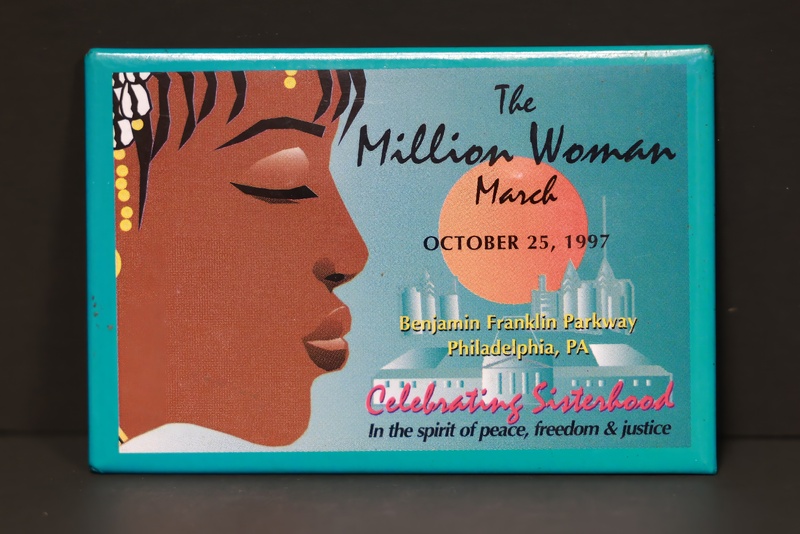

By 1974, Frankye Adams-Johnson, in an effort to avoid interactions with the police after Nuh’s arrest, was living underground for fear that her involvement with him could lead to legal troubles for herself. For the next four years she maintained her life in secrecy and also had her first child. Having that child began to change her priorities and after four years underground she contacted a lawyer who helped her negotiate a 5 year probation, avoiding jail time fully. She stayed in New York until moving home to Jackson in 1999 and while in New York remained active in the movement going to marches and assisting in the efforts to create a Black Panther Party archive at Howard University.

Credits

Garrad Lee, Digital Humanities Program Manager, Margaret Walker Center, Jackson State University

Further Readings

- Library of Congress. “Civil Rights History Project: Frankye Adams Johnson.” YouTube, 21 Feb. 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=JPQ0qh5dgFY.

- Friends of the New York Three, “"Prisoners of War: The Case of the New York Three",” Roz Payne Sixties Archive, accessed February 19, 2025, https://rozsixties.unl.edu/items/show/451.

- Smith, Micah. “Frankye Adams-Johnson.” Jackson Free Press, 20 Oct. 2016, www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2016/oct/20/frankye-adams-johnson/.

How to Cite This Source

"Frankye Adams-Johnson," in HCAC Beta, https://hcacbeta.org/urislug [accessed Month, Day, Year]