Learn How Historically Black Colleges and Universities shaped the course of Black art in the 20th century

When people think about the great flowering of Black art in the 20th century, Harlem often comes to mind. But another epicenter was quietly shaping the course of American art in the Jim Crow South: Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). These institutions—spaces of learning, refuge, and community—were also laboratories for creativity. The Atlanta University Annual Art Exhibitions, founded in 1942, became one of the most important crossroads where Black artists, teachers, and students converged.

The Annuals were not just shows of paintings, sculptures, and prints. They were gatherings where young artists exhibited work for the very first time, where established teachers mentored the next generation, and where institutions like Clark Atlanta, Spelman, Morehouse, and Morris Brown sustained a self-contained art world at a time when White museums and galleries often closed their doors.

Photographs from the exhibitions tell part of the story: Langston Hughes in the crowd at the 1947 show; Dr. Hugh Gloster, president of Morehouse, standing beside student works in 1968; and Atlanta University’s president Dr. T.D. Jarrett admiring an untitled piece in 1969. These were not isolated events—they were points along a longer journey of how HBCUs nurtured, trained, and launched generations of Black artists.

See these images and more at Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library |

Artists Who Shaped The Landscape

|

The story of the Atlanta Annuals cannot be told without the ecosystem that nurtured their artists. Howard University established its art department in 1921, and by the 1930s, HBCU leaders across the South followed suit. In 1931, Atlanta University’s president John Hope recruited Hale Woodruff from Paris to teach at Atlanta University and Spelman—a move that rippled outward as graduates earned advanced degrees and returned to build art programs of their own. Out of this system emerged artists whose careers reveal how deeply intertwined artmaking and teaching were within Black higher education. |

Several award-winning artists from the Atlanta Annuals were products of this system.

Their stories reveal just how deeply intertwined artmaking and teaching were within Black higher education.

-

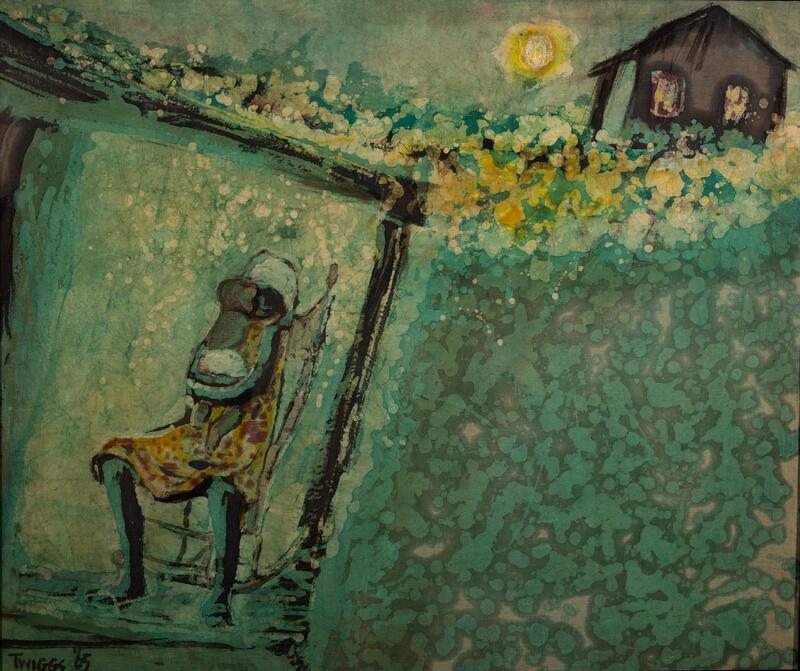

Dr. Leo Twiggs (Claflin University, South Carolina State University) blended batik techniques with Southern iconography, becoming the first Black man to earn a doctorate in art education at the University of Georgia. His piece Lullaby captures the intimacy of Southern life, even as his work has been shown in Harlem, Rome, Dakar, and beyond.

-

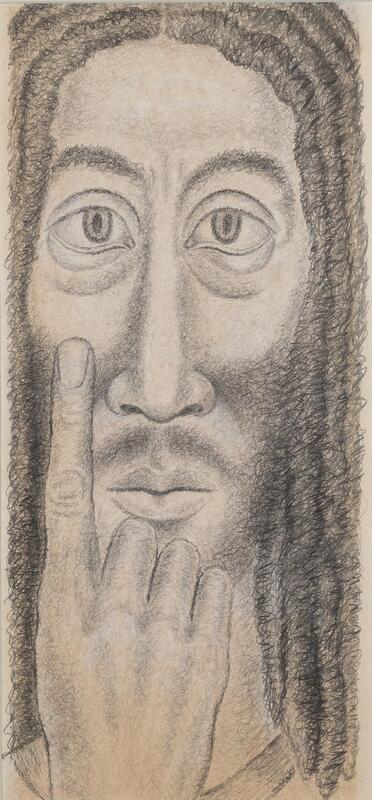

Hayward Oubre (Dillard University, Atlanta University, Winston-Salem State University) bridged painting, sculpture, and wirework. After serving in World War II, he built art departments at multiple HBCUs, training students like Selma Burke and leaving behind award-winning works such as Verily I Say Unto You.

-

John Biggers (Hampton, Texas Southern University) began as a student of Viktor Lowenfield, Elizabeth Catlett, and Hale Woodruff before founding the art department at Texas Southern University. His murals—Web of Life, Songs of the Drinking Gourd, Family Unity—continue to speak powerfully of African diasporic resilience.

-

James Newton (North Carolina Central University, University of Delaware) linked art with activism. His assemblage American Sixties reflects both his military service and the revolutionary spirit of the 1960s. Newton became a central figure in developing Black Studies curricula as well as mentoring students.

-

Anderson Delano Macklin (Lincoln University, Penn State) not only painted—his Flowers and Paper Magnified a masterwork of texture and shadow—but also wrote A Biographical History of African American Artists, A–Z, preserving names and legacies that might otherwise have been forgotten.

-

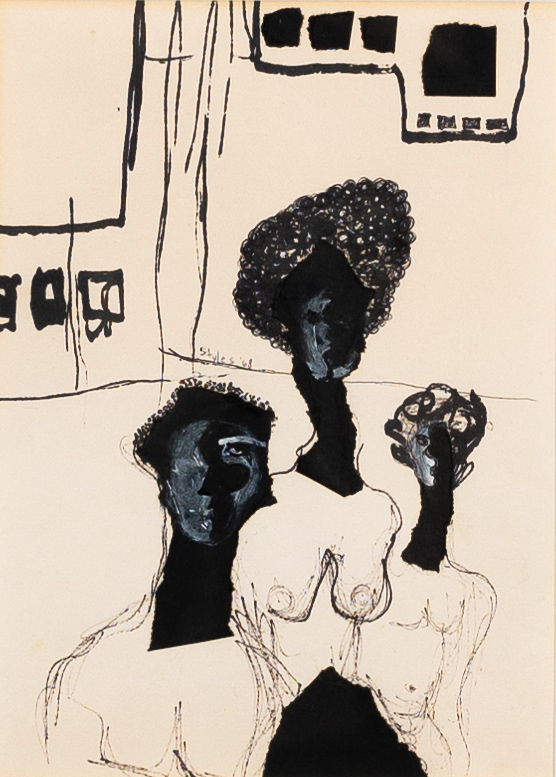

Freddie Styles (Morris Brown College, Atlanta) has lived through and painted Atlanta’s transformations for more than seventy years. His bold colors and collages embody the shifting landscapes of Georgia, both rural and urban.

-

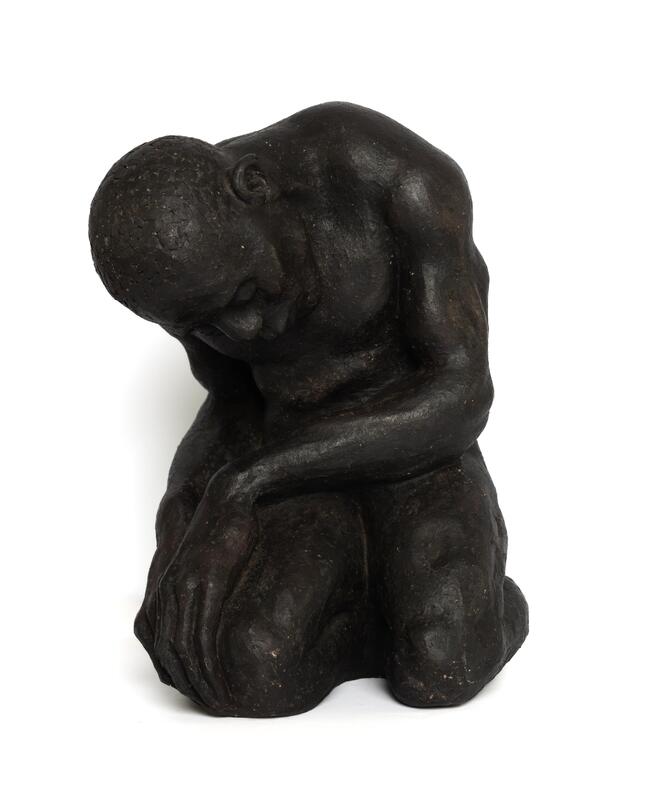

Gregory Ridley, Jr. (Fisk University, Tennessee State) studied with Aaron Douglas and went on to master painting and sculpture. His work and teaching career reflected a lifetime commitment to HBCU art departments.

-

Jimmie Mosely (Florida A&M, Texas Southern, Maryland State) chronicled the Black diasporic experience in works like Johannesburg, while also building fine arts departments and serving as president of the National Conference of Artists.

-

John Howard (Alcorn College, Atlanta University, University of Arkansas Pine Bluff) took his training under Hale Woodruff back to Arkansas, where he founded a program that nurtured rural Black artists for decades. His Arkansas Landscape roots HBCU artistry in place, community, and everyday life.

Art Between Civil Rights and Black Power

The Annuals flourished during a period of seismic change. As the Civil Rights Movement gave way to Black Power and the Black Arts Movement, many artists faced a choice: pursue mainstream recognition in integrated art markets, or remain grounded in Black institutions. Many did both. They exhibited at the Met and the Smithsonian while still teaching in classrooms at Southern HBCUs.

This dual commitment—to art and to education—defined the HBCU arts tradition. For these artists, teaching was not a distraction from art but an extension of it, a way of ensuring that the next generation had tools to create, critique, and imagine.

Continuing the Legacy

The Atlanta University Annuals may have ended in 1970, but their legacy is still alive. Today, the Clark Atlanta University Art Museum and other HBCU collections continue to preserve and exhibit the work of these artists. More importantly, they serve as living archives of a story that is still unfolding.

Every brushstroke, mural, and sculpture reminds us that the story of Black art in America is inseparable from the story of HBCUs. They were, and remain, the first patrons of African American art.

Credits

Shyheim Williams, Clark Atlanta University Art Museum

Further Readings

-

“HBCUs: The First Patrons of African American Art,” Black Art in America — An article exploring how Historically Black Colleges and Universities served as early supporters, collectors, and educators in the African American art world.

-

“20 Top HBCU Art Programs,” The Hundred-Seven (September 2020) — A curated list of leading art programs at HBCUs, examining their histories, offerings, and current influence.

-

Powell, R. J., To Conserve a Legacy: American Art from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (MIT Press, 1999) — A comprehensive survey and analysis of works held in HBCU collections, tracing how these institutions have preserved and promoted important pieces of African American art history.

How to Cite This Source

"All Roads Lead…: Exploring HBCU Arts Engagement through the Atlanta University Annuals," in HCAC Beta, https://hcacbeta.org/urislug [accessed Month, Day, Year]