Women of the Atlanta University Annual Art Exhibitions (1942–1970)

Introduction

The Atlanta University Annual Art Exhibition was one of the longest-running juried shows for Black artists in the United States. While Hale Woodruff is often credited with its success, the real story is richer and more collaborative. Women—whether as artists, administrators, jurors, or patrons—were essential to the show’s longevity. From its beginnings in 1942 until its final year in 1970, they submitted daring works, won awards, and purchased art that seeded what would become the Clark Atlanta University Art Museum. Their commitment made the Annuals a crucial platform at a time when most galleries and museums excluded Black artists.

This page highlights some of the women whose lives and careers intersected with the Annuals, tracing their artistic journeys across three decades.

Opening Years (1942–1950)

From the first exhibition, Black women artists stepped forward, claiming space in a competitive and often male-dominated field. When the Annuals expanded beyond painting to include sculpture and prints, new opportunities emerged for women to be recognized in full range.

Take Rose Piper, born in the Bronx in 1917, whose early career carried the sounds of the Blues into her canvases. Her award-winning Grievin’ Hearted (1948) was not just a painting but a statement of belonging, proof that she could hold her own in the Black New York art scene. Later in life, Piper turned to textiles and design, but her meticulous attention to detail echoed the rhythms she had first developed in paint.

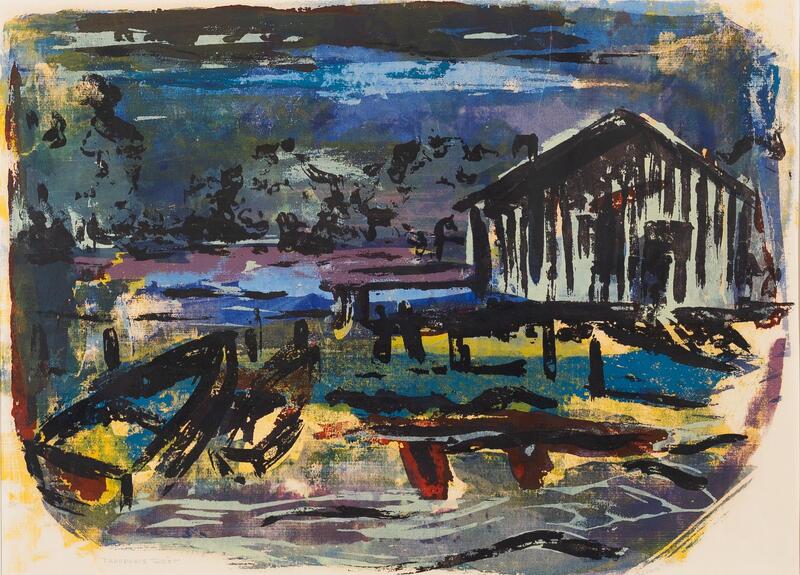

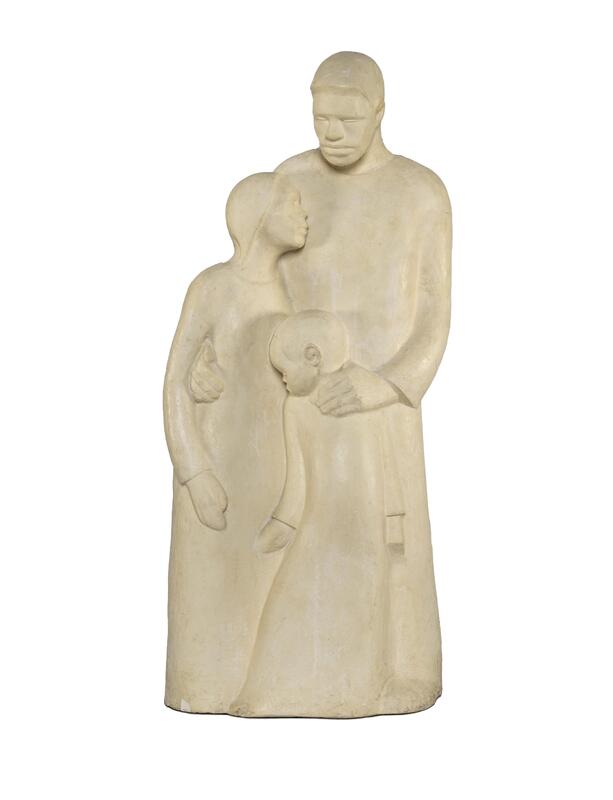

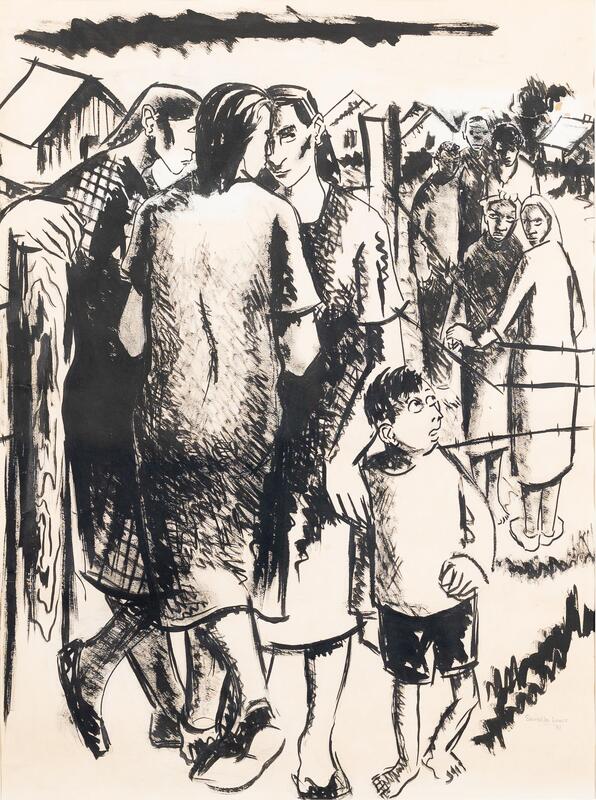

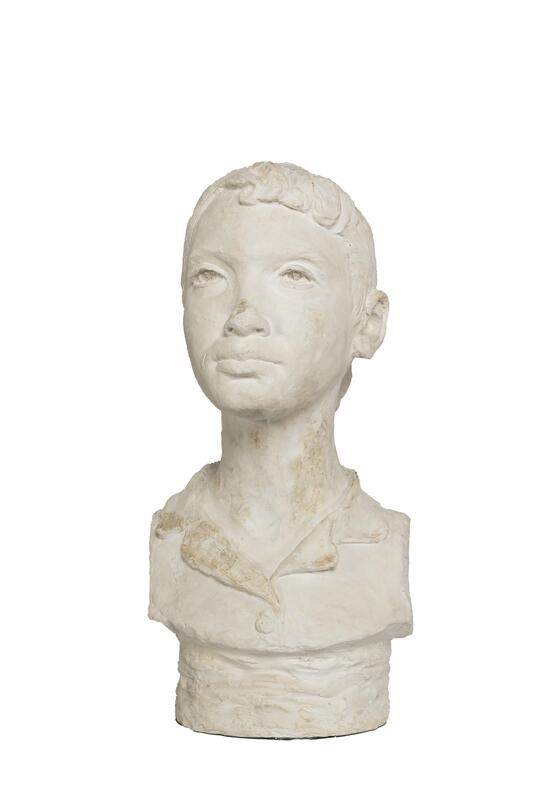

Samella Sanders Lewis, raised in New Orleans, followed a different path. She became the first Black woman to earn a doctorate in Art History, and her deep belief in the power of art as cultural memory infused everything she created. Her prints and sculptures, such as The Family (1947) and Trapper’s Rest (1956), centered Black figures and landscapes, while her work as a teacher and later museum founder transformed the visibility of Black artists across the country.

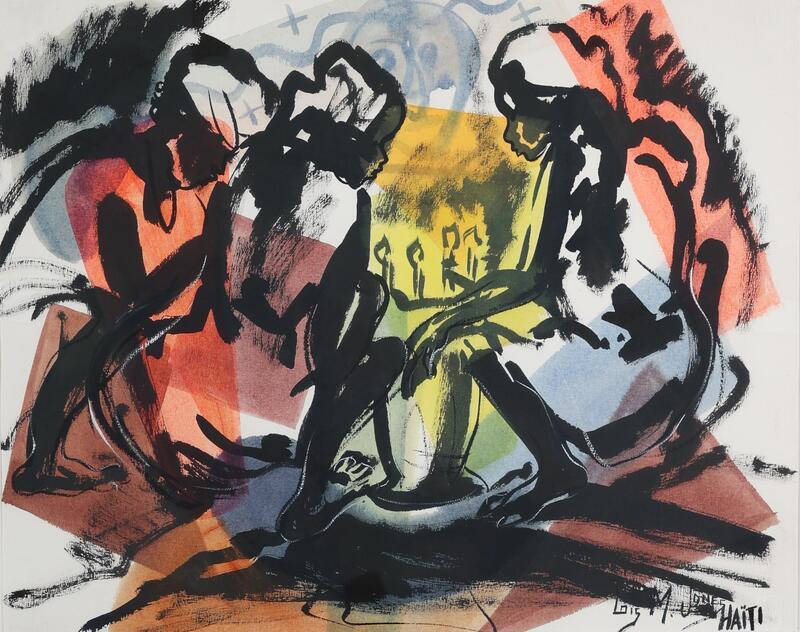

Meanwhile, Loïs Mailou Jones brought an international sensibility to the Annuals. Encouraged early on by Harlem Renaissance sculptor Meta Warrick Fuller, Jones studied in France and Haiti, where she connected with Négritude thinkers. African masks and diasporic motifs appeared again and again in her award-winning works, including Egyptian Heritage (1955). As the first woman recognized by the Annuals, she proved that women’s art was equal to, and often exceeded, the celebrated work of their male peers.

Middle Years (1951–1960)

By the 1950s, the Annuals had become a space of resilience. Amid segregation and violence, art was both a shield and a form of protest. In 1955, four women received awards in a single year—a record that testified to their growing influence.

Geraldine McCullough, trained at the Art Institute of Chicago, captured both hardship and hope. In her award-winning Of Hope (1957), a yellow flower held by a central figure glows against a bleak background, a symbol of optimism in an era of repression. Later, her welded metal sculpture Phoenix drew on scrap materials to evoke rebirth from racial violence.

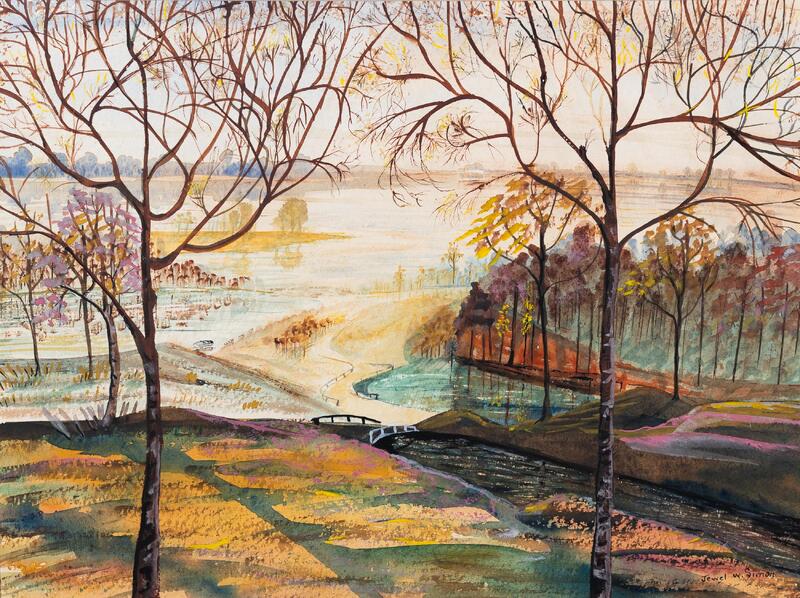

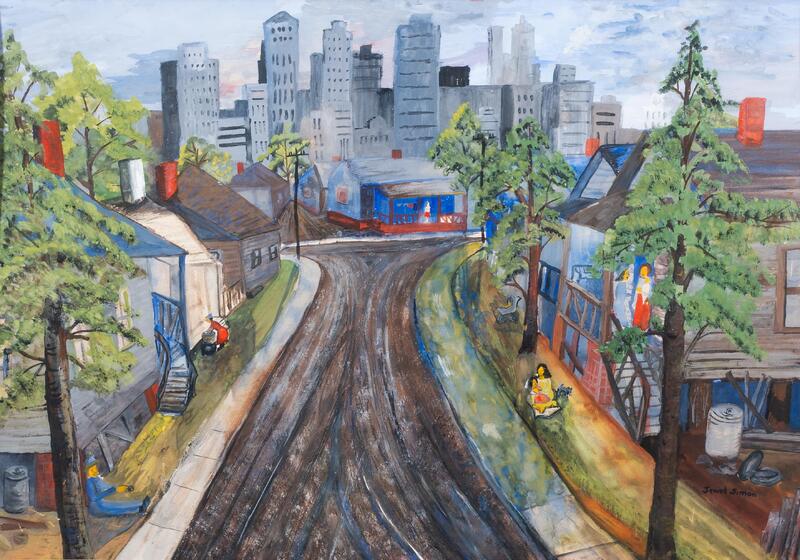

Jewel Woodard Simon, a Houston-born artist who studied under Hale Woodruff and Alice Dunbar, became the most decorated woman of the Annuals. Her vibrant landscapes—City Slums (1953) and February Lace (1962)—radiate movement and color, blending the urban and the natural. Though she never pursued art full-time, her record of awards left an indelible mark.

Another standout, Irene V. Clark, won first prize in oils in 1956 with My Great, Great, Great Grandfather’s Cousin. Her work often drew on African history and memory, layered in shades of blue that were at once melancholic and bold. Clark’s later career took her into gallery direction and exhibitions nationwide, leaving behind a legacy that, though under-documented, is preserved in collections across the country.

Closing Era (1961–1970)

As the Annuals entered their final decade, they intersected with the energy of Black Power and Women’s Liberation. Women artists used the exhibition to carve out visions of freedom, even as awards for women became less frequent.

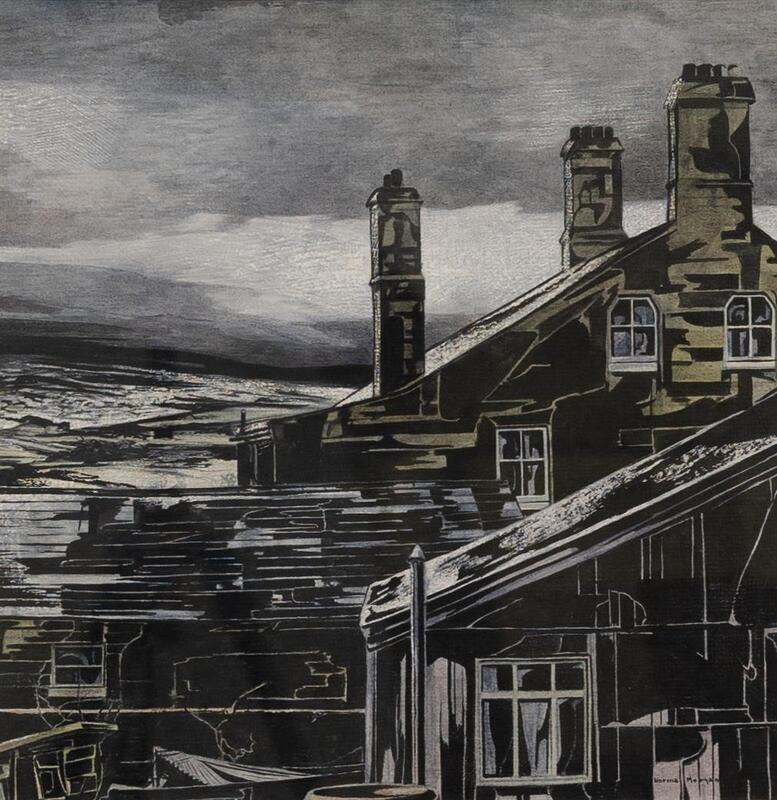

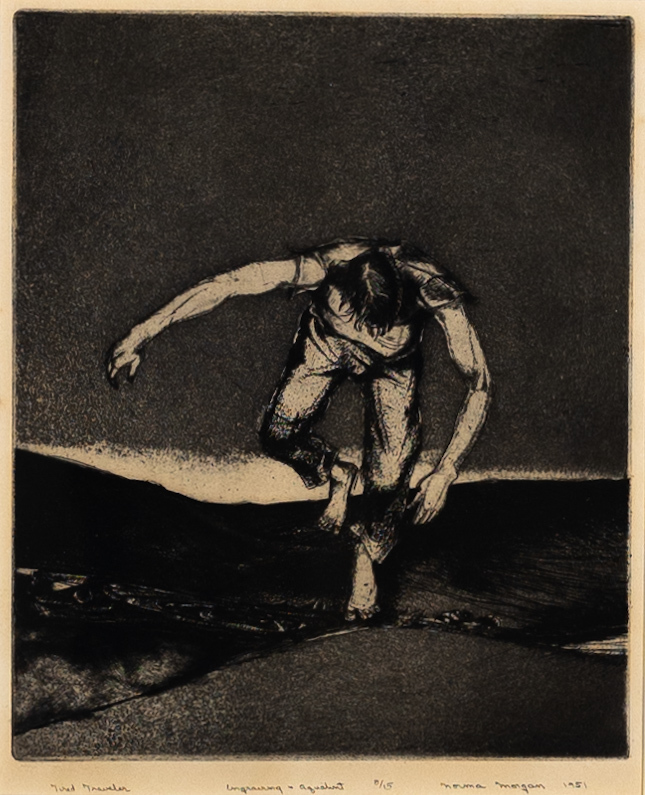

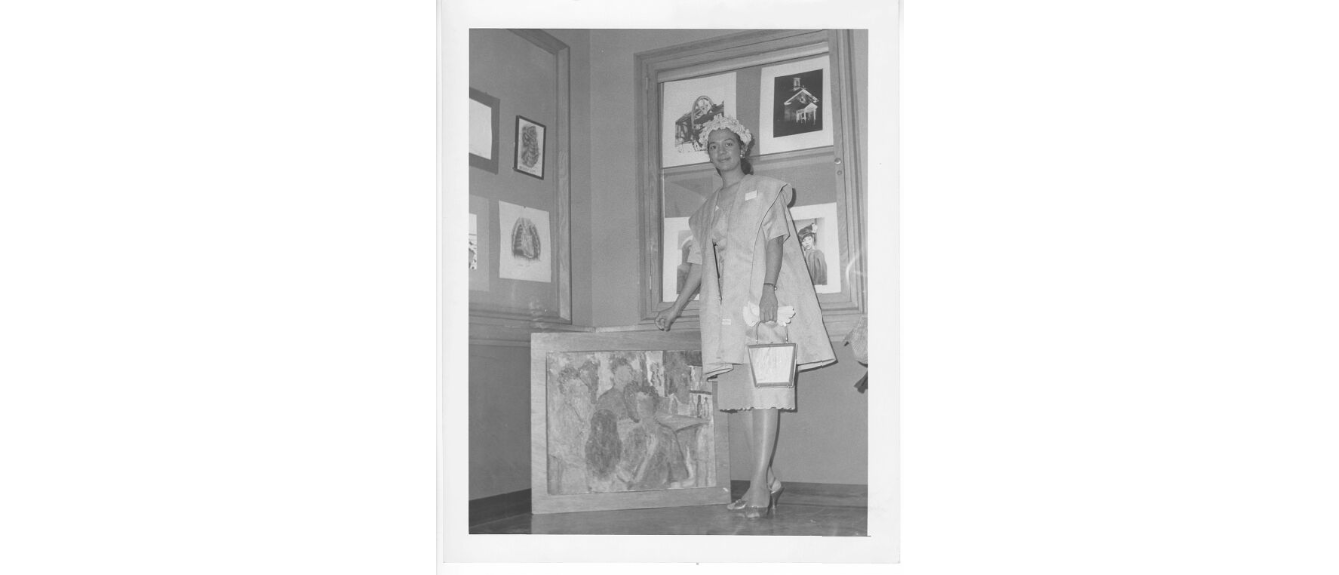

Norma Morgan, raised in New Haven, Connecticut, studied with Hans Hofmann before shifting from abstraction to the textured landscapes that defined her career. Her Tired Traveler (1962) and Ghost Light (1963) earned recognition at the Annuals and later carried her to the world stage at the First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal, in 1966.

Lucille Malika Roberts, a Washington, D.C. native and student of Loïs Mailou Jones, infused her art with diasporic connections. After travels across Africa, she adopted the Swahili middle name “Malika,” meaning queen. Her painting Street in Senegal (1967) reflects those journeys, blending memory, heritage, and identity.

Shirley Bolton, from Lexington, Georgia, exhibited in every Annual of the final decade. Her textured cityscapes, such as Tenement (1970), often layered cardboard over paint for added dimension. Though she died young, her tenure as a professor and her publications on African American art pedagogy left a lasting imprint.

The women of the Atlanta Annuals were more than participants; they were cultural architects who made the exhibitions possible and meaningful. Their contributions remind us that the history of Black art cannot be told without them.

We must also remember those whose legacies extend beyond this page—Irabell J. Cotton, Margaret Burroughs, Elizabeth Catlett, and Jenelsie Holloway among them. Their works remain essential to the story of African American art and continue to inspire new generations.

Visitors are encouraged to see these works in person at the Clark Atlanta University Art Museum, where the spirit of the Annuals lives on.

Credits

Mia Sturdivant, Clark Atlanta University

Shyheim Williams, Clark Atlanta University

Further Readings

How to Cite This Source

"Women of the Atlanta University Annual Art Exhibitions (1942–1970)," in HCAC Beta, https://hcacbeta.org/urislug [accessed Month, Day, Year]