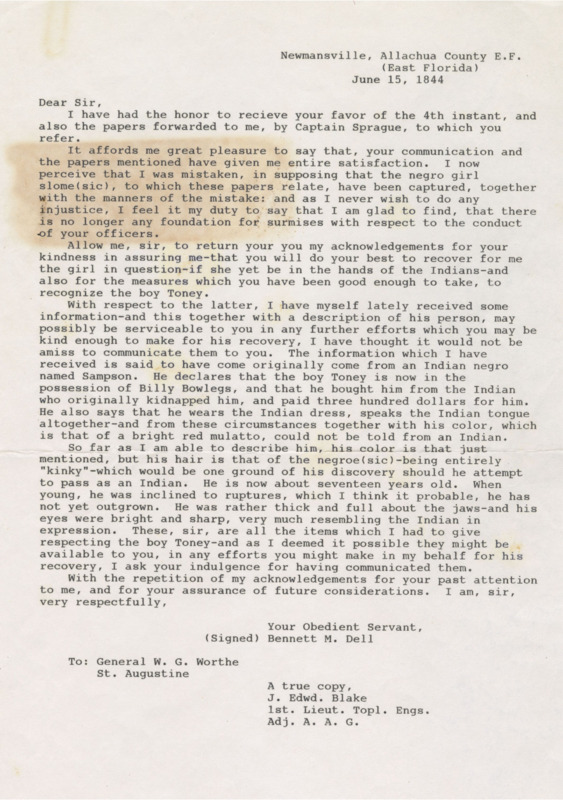

Featured Historical Correspondence – June 15, 1844

In the summer of 1844, a letter traveled from Newnansville, East Florida (present-day Alachua County) to St. Augustine.

Its author, Bennett M. Dell, wrote to General W. G. Worthe in the aftermath of the Second Seminole War. At first glance, the letter seems like routine communication between two white officials. But on closer reading, it reveals the entangled realities of slavery, Indigenous resistance, and settler colonialism in territorial Florida.

Searching for the Enslaved

In the letter, Dell opens by addressing earlier correspondence about an enslaved girl he had mistakenly believed was already in custody. He expresses gratitude for Worthe’s efforts to recover her if she remained in the hands of Native Americans. This brief acknowledgment quickly shifts to the real focus of his letter: another enslaved person named Toney.

Toney’s Story on Paper

The bulk of the letter is a detailed description of Toney, a seventeen-year-old of mixed African and Native ancestry. Dell describes his physical features, mannerisms, and speech—evidence of the racialized identification practices that marked enslaved people’s lives on the page. What emerges is a portrait not of Toney as a full human being, but of Toney as property to be tracked and reclaimed.

Dell recounts how Toney was captured by an Indigenous man named Sampson, sold to another named Billy Bowlegs, and later ransomed for three hundred dollars. The letter treats this series of violent exchanges as transactions in a marketplace, matter-of-factly recording the movement of a young man’s life between captivity, sale, and attempted recovery.

A Window into Florida’s Racial Landscape

This single document highlights the overlap of three forces in territorial Florida: the expansion of slavery, the displacement of Indigenous peoples, and the fragile hold of white settlers trying to secure authority in the aftermath of war. For people like Dell, the recovery of enslaved people was not only an economic priority but also a political assertion of control. For the enslaved themselves, including Toney, these struggles determined the contours of survival and identity in a landscape of conflict.

Why This Letter Matters

The letter of June 15, 1844, is more than an exchange between two men of power. It is a record of how slavery extended into every corner of Florida’s social and political life. It shows how enslaved people were identified, pursued, and valued—and how their lives intersected with Indigenous communities navigating their own survival amid colonization and displacement.

As an artifact, the letter reminds us that the archive of slavery is filled with documents written not by the enslaved but about them. To read it today is to confront both the violence of categorization and the resilience of the people whose lives appear in its lines. Toney’s story, filtered through the language of his enslavers, becomes a testament to the entangled history of race, power, and resistance in nineteenth-century Florida.

Credits

<Insert Name>, <Insert Title>, FAMU Meek-Eaton Black Archives

FAMU Slavery Papers

Discover the full collection of papers associated with slavery in the American South and other rare documents and objects at the Meek-Eaton Black Archives Collection, The Florida A&M University.

Explore Full Collection →How to Cite This Source

"Title," in HCAC Beta, https://hcacbeta.org/urislug [accessed Month, Day, Year]