Remembering Rosewood: History, Memory, and the Fight for Justice

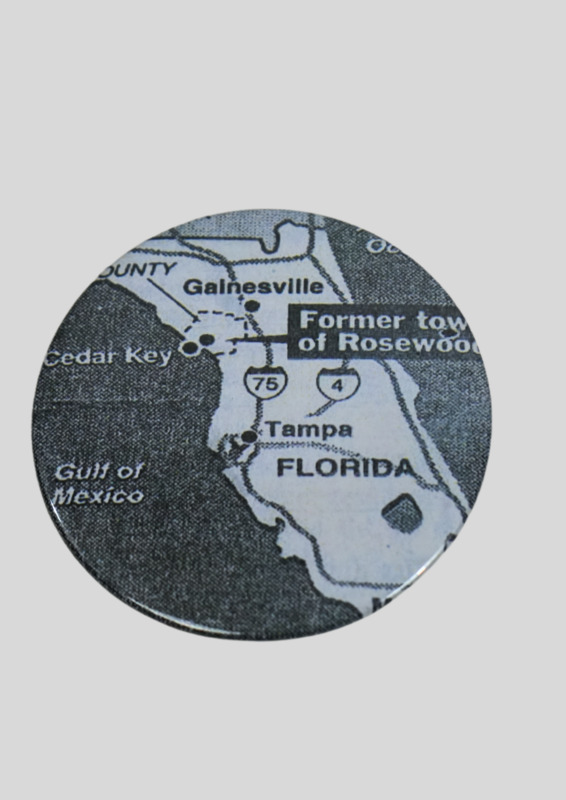

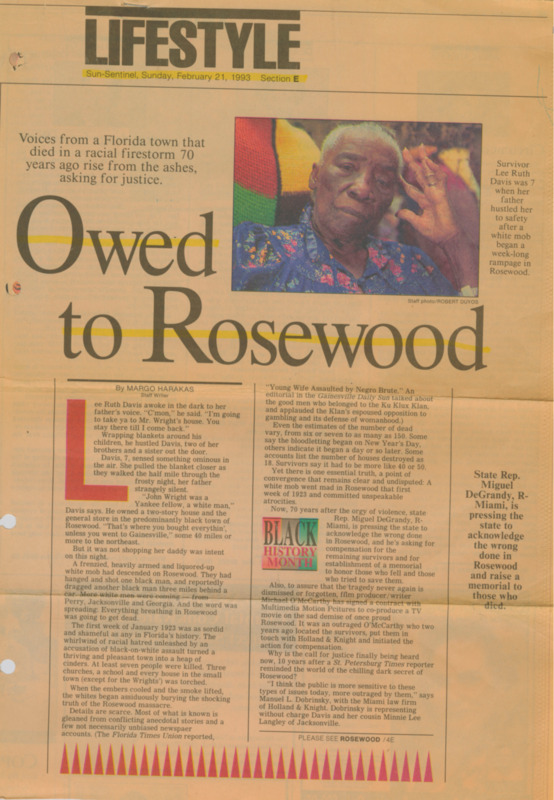

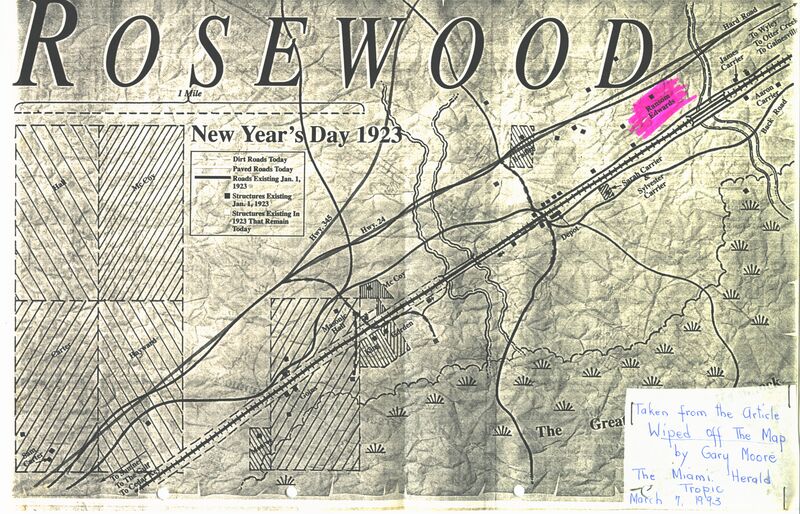

In January 1923, the small Black community of Rosewood, Florida, was destroyed in one of the most violent episodes of racial terror in U.S. history. What began with a false accusation escalated into mob violence, arson, and murder—erasing a once-thriving town from the map. For decades, the story of Rosewood lived primarily in the memories of survivors and descendants, hidden from the broader public. Only in the late twentieth century did the state of Florida begin to reckon with its role in the tragedy.

Today, more than a century later, Rosewood is not only remembered—it is commemorated, studied, and honored as part of a larger struggle to confront racial violence and pursue justice.

1923: The Destruction of Rosewood

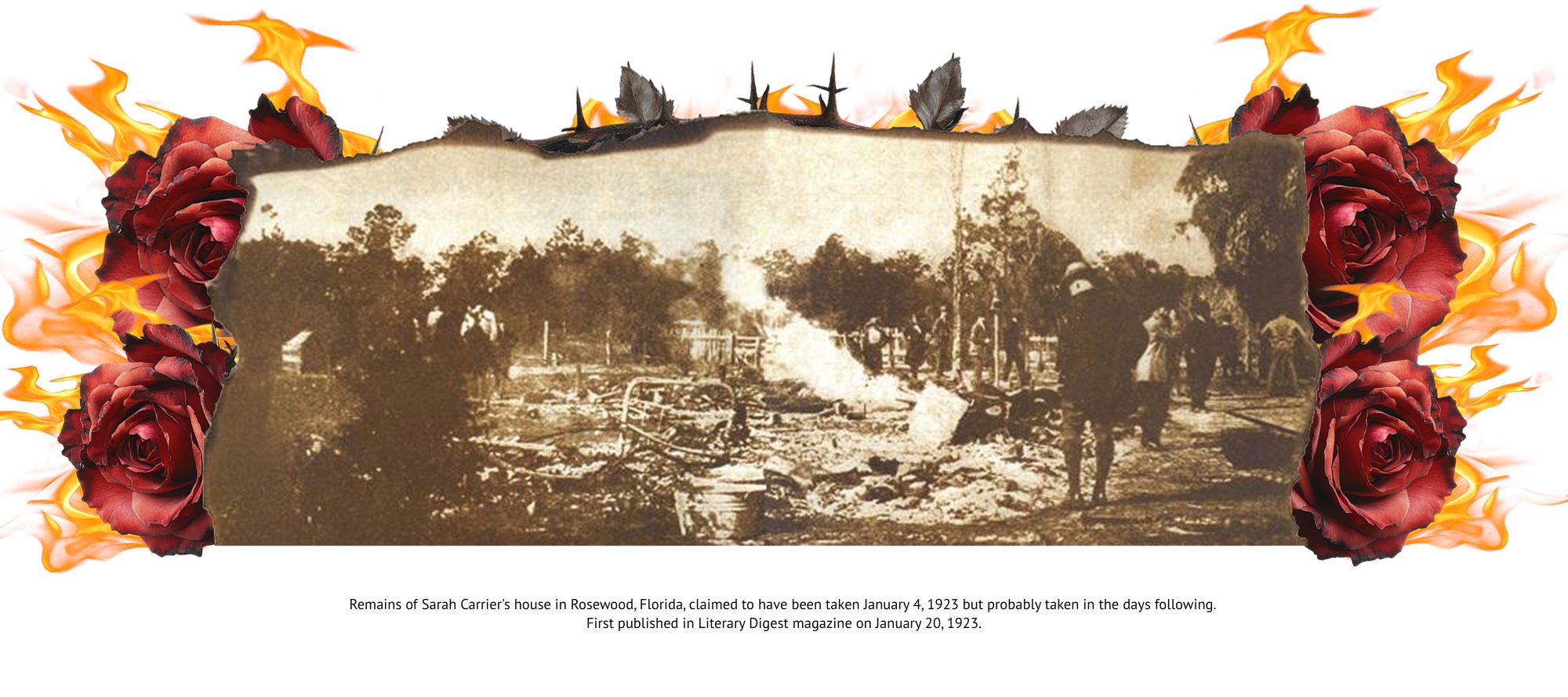

On January 4, 1923, a white woman in the neighboring town of Sumner, Fannie Taylor, claimed she had been assaulted by a Black man. No evidence supported her story, but it set off a wave of violence. White mobs descended on Rosewood, looting and burning homes, churches, and businesses. Black residents fled into nearby swamps, hiding for days in fear of their lives.

At least eight people were killed—though some accounts suggest the number was higher. Law enforcement failed to protect Rosewood’s residents, and in some cases, officers were reported to have aided or turned a blind eye to the violence. By the end of the week, Rosewood lay in ruins, its families scattered. The community that had once supported schools, businesses, and churches was erased, and its history silenced.

1993: Investigation and the Path to Reparations

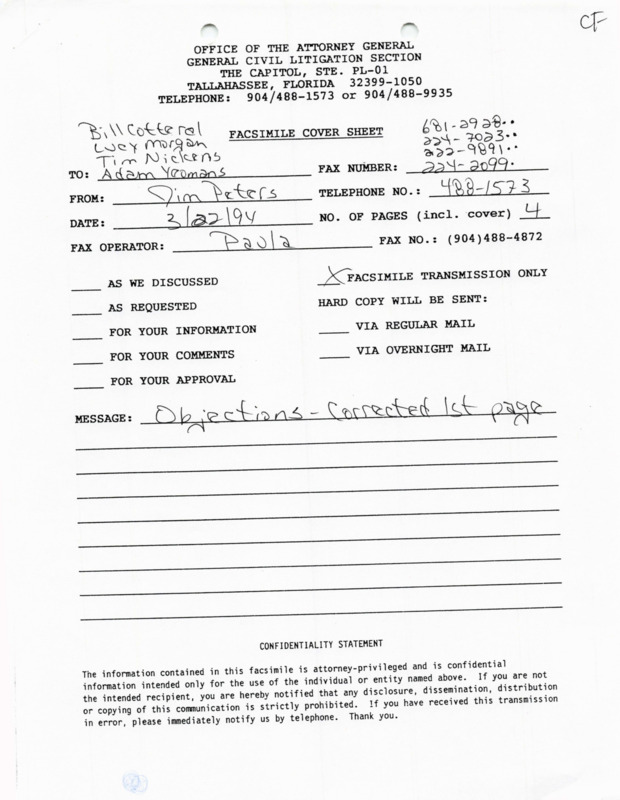

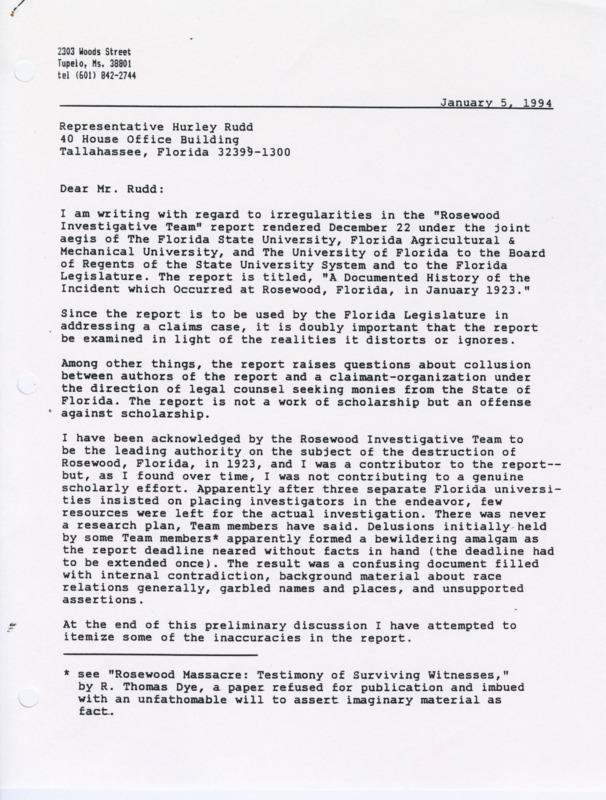

For seventy years, the events of Rosewood remained largely absent from official histories. That began to change in 1993, when the Florida Legislature commissioned a formal investigation into the massacre. Scholars from Florida A&M University, Florida State University, and the University of Florida worked together to collect survivor testimony, archival records, and historical evidence. The investigation was led by historian Dr. Maxine Jones of Florida State.

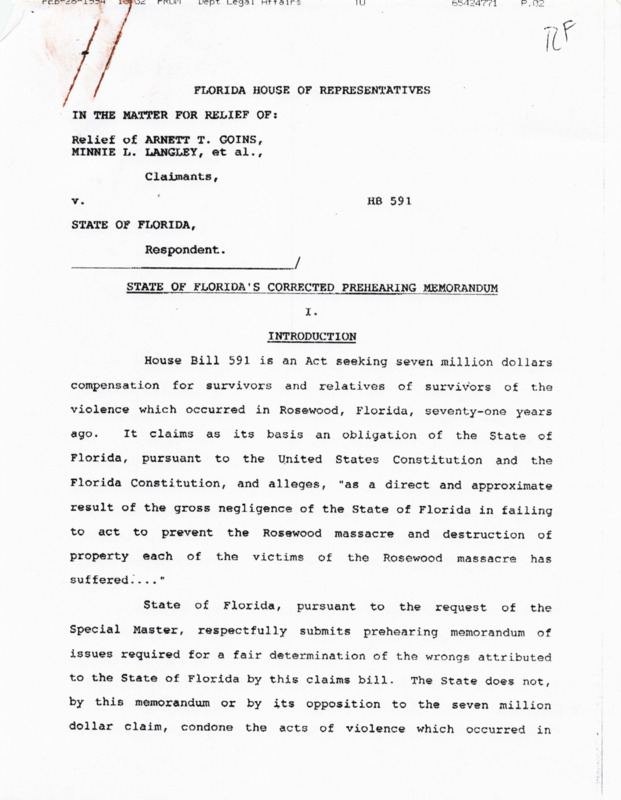

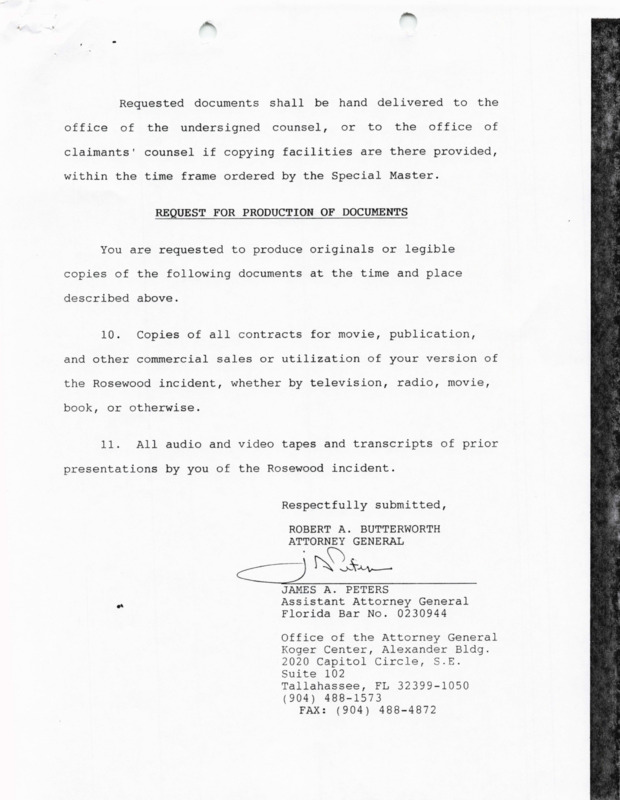

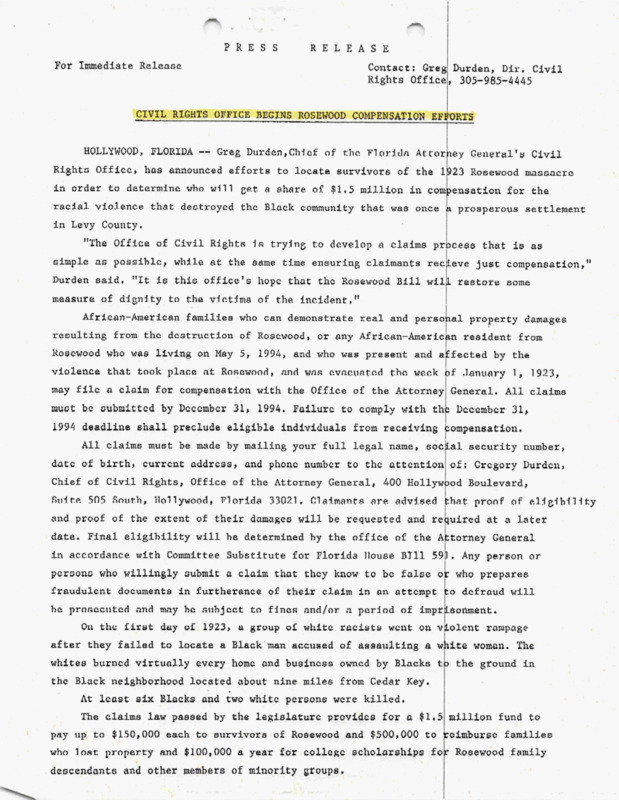

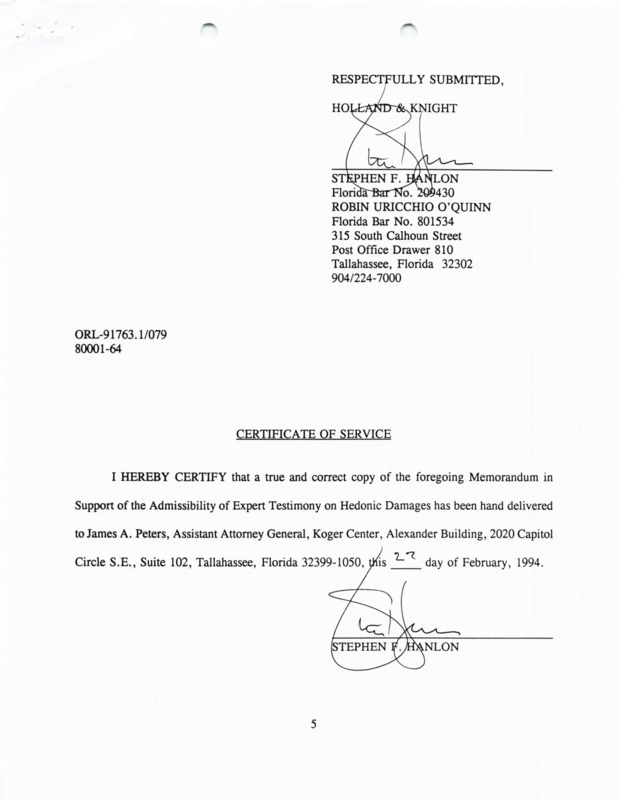

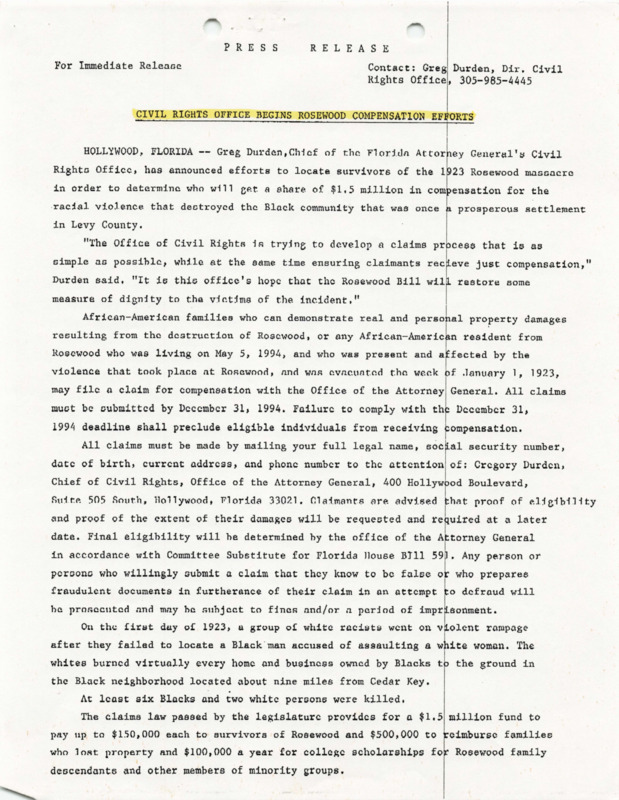

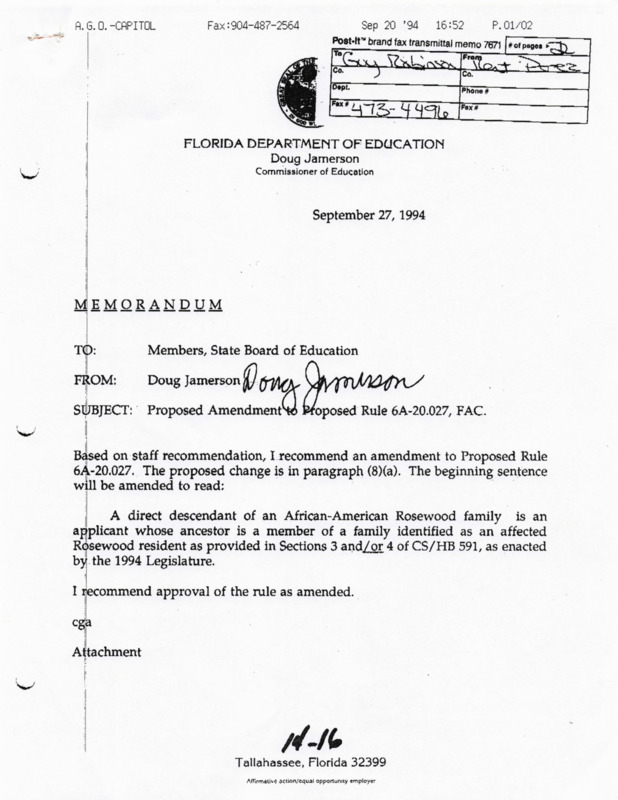

The resulting report, A Documented History of the Incident Which Occurred at Rosewood, Florida in January 1923, became a landmark in uncovering the truth. It not only confirmed the violence and devastation but also made clear the state's failure to act. Building on these findings, Florida lawmakers passed legislation in 1994 to compensate survivors and their descendants—making Florida the first U.S. state to pay reparations for racial violence.

That outcome was far from inevitable. Two earlier bills introduced in 1993 failed before House Bill 591 was passed. One bill, more symbolic than substantive, lacked funding or evidence and never made it out of committee. Another, House Bill 2425, proposed a modest grant for investigation but fell short in the Senate. These struggles reflected the political tensions surrounding reparations, even in the face of overwhelming historical evidence.

2025: A Tradition of Remembrance

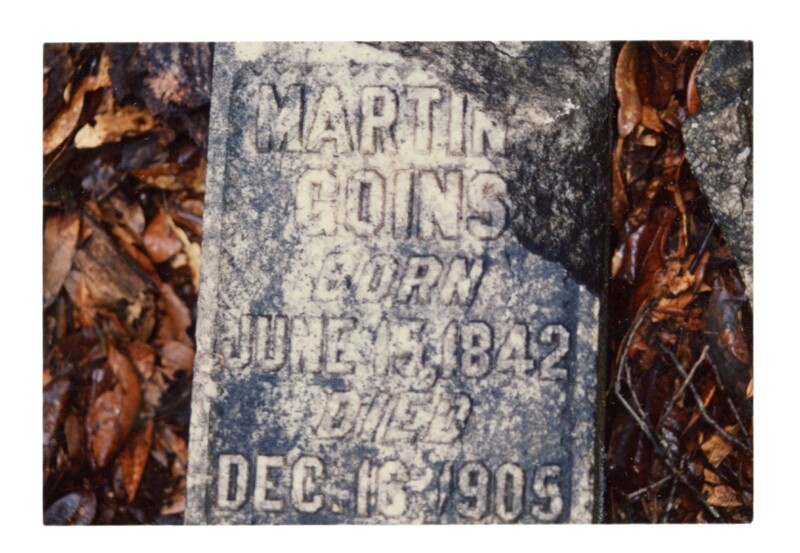

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the first Rosewood family gathering, held in 1985. What began as a small reunion has grown into an annual tradition where descendants come together to honor their ancestors, share stories, and celebrate resilience.

These gatherings are not only moments of remembrance but also spaces for education and advocacy. Through storytelling, meals, and community connection, descendants keep the memory of Rosewood alive while drawing attention to the broader legacies of racial violence. In doing so, they ensure that Rosewood’s story is not confined to tragedy but continues as a testament to survival, unity, and cultural preservation.

Media, Memory, and Public Understanding

The way Rosewood has been remembered owes much to the press. Early twentieth-century newspapers often misrepresented the violence, portraying Black residents as aggressors and downplaying the scale of destruction. These distortions shaped public perception for decades, reinforcing silence around the massacre.

In contrast, more recent investigative journalism has worked to uncover hidden truths and amplify survivor voices. Taken together, historic and contemporary coverage reveals both the power of the media to obscure and its potential to reclaim history.

Preserving Rosewood’s Legacy

The documents, newspaper articles, and legislative records that survive today tell a story not just of violence, but of persistence. Community members, civil rights leaders, descendants, and lawmakers fought to bring Rosewood into national conversation and secure recognition and reparations. Their efforts remind us that history is not static—it is contested, reclaimed, and carried forward.

The story of Rosewood continues to resonate because it forces us to confront uncomfortable truths while also highlighting the possibility of change. Memory, advocacy, and historical research together have transformed a silenced past into a legacy of resilience and justice.

Credits

<Insert Name>, <Title>, FAMU Meek-Eaton Black Archives

Further Readings

- Dye, R. Thomas. "Rosewood, Florida: The Destruction of an African American Community." The Historian 58, no. 3 (1996): 605–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24449436.

- González-Tennant, Edward, ed. The Rosewood Massacre: An Archaeology and History of Intersectional Violence. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2019.

- Dye, R. Thomas. "The Rosewood Massacre: History and the Making of Public Policy." The Public Historian 19, no. 3 (1997): 25–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/3379554.

How to Cite This Source

"Title," in HCAC Beta, https://hcacbeta.org/urislug [accessed Month, Day, Year]